The Lost Art of Desi Storytelling

By telling age-old stories with new packaging, we can once again make Desi storytelling great again

Mirza-Sahiba. Heer-Ranjha. Sassi-Punnun. Sohni Mahiwal.

No offense to Shakespeare, but these tragic tales of romance might well outshine Romeo and Juliet in a fierce duel.

Perhaps the only advantage Romeo and Juliet has is that these Punjabi folktales were not documented as extensively. Let’s now consider the premakhyan composed by Sufi poets—such as Mulla Daud’s Chandayaan, Narayana Das’s Chitai-Charita, Sheikh Qutban’s Mrigavati, Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s Padmavat, and Mir Manjhan Shattari’s Madhumalati.

Aqsa Ajaz, in her review of Pasha M Khan’s The Broken Spell: Indian Storytelling and the Romance Genre in Persian and Urdu (2019), argues that “such stories were instrumental in shaping their listeners' emotional landscapes.” Ajaz notes that when the colonial regime began consolidating its rule in India during the early nineteenth century, it targeted these local storytelling forms as a site of intervention.

These stories were not entirely forgotten, however. South Asian folktales began to be compiled in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Yet, this compilation was more about gathering information on "natives" for "ethnographic surveillance" rather than genuine preservation. (As George Orwell might put it—Big Brother.)

Even though some folklore texts were published under British rule, post-colonial analysis reveals the politics of translation at play. (On that note, thanks to Edward Said for deepening our understanding of Orientalism and Postcolonial Studies. As the kids say, the OG!)

Returning to the countless tales lost to time…

Storytellers' Bazaar—Lost in Transit

Shogran in Peshawar has long been a bastion of Pakistan’s oral history. Since the days of the Silk Road, this region has been famed for its Qissa Khawani or "storytellers’ bazaar," celebrated for the excellence of its storytellers. The storytellers’ bazaar has been hailed as “the greatest in the East,” and likened to Homer’s Greece.

The story of Saif-ul-Malook—a brave prince who falls in love with a fairy—may be hard to find elsewhere.

Sadly, there is no longer an audience for such tales.

"People usually think I’m crazy when I tell these stories," Naseem, an elderly storyteller, tells Dawn. Unfortunately, the 50-odd tales passed down to him by his father may be lost forever.

This situation brings to mind Piyush Mishra’s portrayal of an aged storyteller in Tamasha. Largely forgotten and scorned, he is rediscovered by a corporate slave, who finds a renewed zest for life through this encounter. This mirrors how the Urdu storytelling form Dastangoi has revived art and literature.

Recently, Dastangos Mehmood Faruquii and Poonam Girdhani translated Ret-Samadhi, the Booker Prize (2022)-winning novel in Hindi by well-known author Geetanjali Shree, into a Dastangoi performance.

Similarly, actor-director Ajitesh Gupta applied the Dastangoi storytelling form to narrate the story of renowned Sufi poet Amir Khusrau on stage.

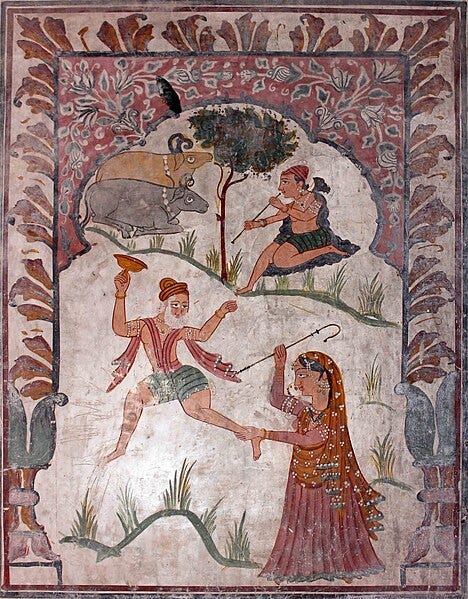

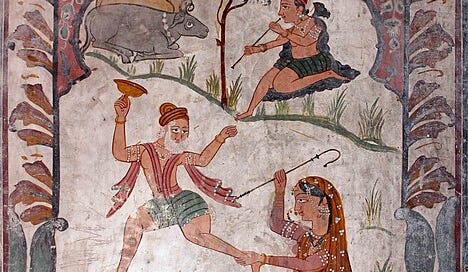

Meanwhile, Sushmita Singha, co-founder of Udaipur Tales International Storytelling Festival has featured a Tamil horror folk story and Rajasthani Phad artists in the festival lineup.

In Mumbai, Usha Venkatraman is dedicated to contemporaryizing age-old oral narratives through the Mumbai Storytellers Society.

And saat samandar paar, nonprofit Peerbagh is preserving South Asian oral storytelling traditions, bringing the magic of South Asian folktales to Desi kids growing up in the United States!

So, there you have it: by presenting age-old stories in a fresh format, we can revive the greatness of Desi storytelling.

After all, wouldn’t it be exciting to introduce kids to Amir Hamza and Tilism-e-Hoshruba, and let them explore the realms of wizards, djinns, and fairies with the same enthusiasm as they do with Harry Potter?

As the kids say, let’s make Chitra Kathas … Amar again!

This is so beautifully put. ✨